This morning I read a short article from Allawi in The Chronicle Review (part of The Chronicle of Higher Education). In "Islamic Civilization in Peril," Allawi introduces his "insiders" understanding of the crisis facing Islamic peoples across the world.

Allawi, a senior visiting fellow at Princeton University, has just been named one of the first two Gebran G. Tueni human-rights fellows at the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. I believe these thoughts are tantalizing pieces from his fuller work, The Crisis of Islamic Civilization, was published by Yale University Press in March, which came out in March of this year.

Allawi, a senior visiting fellow at Princeton University, has just been named one of the first two Gebran G. Tueni human-rights fellows at the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. I believe these thoughts are tantalizing pieces from his fuller work, The Crisis of Islamic Civilization, was published by Yale University Press in March, which came out in March of this year.Allawi writes:

The crisis in Islamic civilization arises in part from the fact that Muslims have been unable to chart their own path into contemporary life. Islam as a religion — or even as a remnant of a civilization — has never fully surrendered to the demands of a desacralized world. Those who rule over Muslims may behave atrociously, continuing a venerable tradition of misrule, violence, and corruption that has long plagued the Muslim world, but tantalizing thoughts of "what might be" still reverberate among the masses — and even among some of the elite.

Islam's encounter with the West and the ascendant forces of modernity have made deep inroads into the outer world of Islam and, equally important, into the minds of Muslims. Some may deny it and fight numerous rear-guard actions, but this reality cannot be effaced until Muslims confront another harsh fact: All civilizations have an inner and outer aspect, an inner world of beliefs, ideas, and values that inform the outer aspects of institutions, laws, government, and culture. But the inner dimensions of Islam no longer have the significance or power to shape the outer world in which most Muslims live. Most Muslims — knowingly or not — have lost sight of the centrality of sacredness to their historic civilization. The Muslim world has effectively become desacralized, and that has changed how Muslims think, believe, and behave. Islam's outer expressions — laws, institutions, governing structures, economic and cultural principles — have been in constant retreat.

The insatiable pursuit of ever-rising standards of living, coupled with an almost fetishistic belief in science and technology, is a nearly universal condition. The West has accepted secularization as an inevitable consequence of increasing wealth and power. That same recipe is now being offered to Muslims. Liberal reformers in the Muslim world, and their allies beyond, are in effect calling for a Christianization of Islam: concede the public arena to secularism and acknowledge that the break between Islam's sacred interior world and the profane external world is definitive and legitimate. The reformers, advocates of Muslim liberal democracy, are at least honest in that they forthrightly call for the wholesale adoption of the institutions and processes of modernity. But their vision of Islamic civilization is empty — a vague spirituality wafting over a society with a shallow cultural distinctiveness, one that has effectively merged with the dominant order.

The radical Islamists, on the other hand, and even the rank and file of so-called "rationalist" Muslims who insist that Islam has all the elements of Western-style humanism already embedded in it, suffer from a different conceit — namely that a happy compromise can be fashioned between Islam and modernity simply by running modern ideas through the filter of the Shariah: What is acceptable will be embraced, and what is not will be rejected. That approach, which has been entertained for more than a century, has produced neither material progress nor the foundations of a revivified Islamic civilization. The fundamental conundrum facing both rationalists and radicals is that the forces of modernity are the product of a different and ascendant civilizational order. Those forces can be internalized successfully only if they are refashioned, and then transcended, in a uniquely Islamic framework.

Such a framework must be rooted explicitly in the Islamic virtues of justice, moderation, the respectful accommodation of other cultures and religions, and the rejection of oppression and gross inequalities. Those immutable principles are spelled out in the Koran. They are milestones for the believers' pathways to God. They should guide an ethical rereading of the Shariah that will not only revitalize Islam's outer world, but also bring Islam closer to providing a new, constructive, and potentially appealing response to the growing problems facing humanity — including environmental degradation, the coarsening of public life, economic inequity among nations and peoples, and overconsumption. The Shariah has traditionally been pitted against modern practices and values, with the implication that it should give way to the prevailing ethos. Or the Shariah has been seen in entirely static terms, a blueprint for reviving some golden age of Islam. The latter is the approach of fundamentalist Muslims.

But an Islam reimagined along the lines sketched above can go beyond the travesty that is "Islamic banking" and produce institutions and enterprises that emphasize risk-sharing and cooperative finance. It can push for technological innovations that focus on conservation. In the hard sciences, Islam can privilege research that seeks to reveal the unseen substructures that underlie the physical world — what the great theoretical physicist David Bohm called the "implicate order," which has not been investigated with the necessary energy because it counters the prevailing methods of scientific inquiry. Islam can open up entirely new vistas to find unity and wholeness in the natural world.

Muslims cannot simply partake of the technological fruits of modern civilization while simultaneously rejecting or questioning its premises. That makes them nothing more than inert consumers of the effort and creativity of others — even if they continue to smugly assert the superiority of their spiritual ways. That is the ultimate fallacy of the Islamists. Alternatively, Muslims might choose to package the products of Western civilization in ways that are culturally or politically acceptable to their own societies. They can even participate in the dominant civilizational order and risk fatally undermining whatever remains of Muslims' basic identity and autonomy. That appears to be the path of the Gulf states, which have exuberantly embraced a frantic hypermodernity that is scantily garbed in Islamic idioms. This path also appeals to the Westernized professional classes who view their Islam as little more than a cultural ornament.

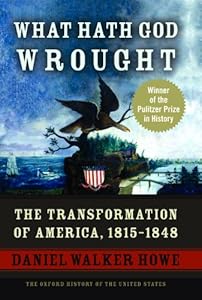

To see more of Allawi's analysis, check out his new book. I found a preview available through Google Books online --